-

I have been in one of those pessimistic moods of late (and this was before last Thursday), where I question the value of being a writer; that my job doesn't save lives, or put fires out, or shape economic policy. It's one of those times where I can't shake Mishima's statement that the writer is the ultimate voyeur; that we sit around on the fringes of the action, making prurient notes in our notebooks, and then spilling our thoughts, whether they be of schadenfreude, or of joie de vivre, for our own private benefit.

I am lucky. My father founded and ran a group of EFL schools in Kent in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Since my mother worked there too and since my parents couldn't afford a baby sitter, my brother and I would often happily be dragged along to functions of various kinds. I'm sure they felt it was good for us to meet people from other cultures, growing up as we did in a very white part of England, but the accidental wisdom of this cannot be underestimated. My brother and I would stand around while we were shyly introduced to young students from around the world who'd come to learn English at my Dad's schools. I have fond memories of meeting many German, French, Italian, Swedish, Russian and Greek students amongst others from Europe, as well as people from further away: Iranians, Iraqis, Saudis, Nigerians, Egyptians, Japanese and so on and so on, and without fail, all I can remember are happy faces, warm smiles, and friendly handshakes. I learnt very early on that there is nothing to fear in the Other, per se; that there are kind and generous people across the world.

So today, and focussing for obvious reasons on Europe, here are my favourite European novels.

FINLAND (written in Swedish)

The Summer Book - Tove Jansson

As wonderful as Jansson's Moomin books are, my favourite of her works are The Summer Book and The Winter Book - both depicting life on one of the myriad small islands in the Baltic between Sweden and Finland, and the relationship between an elderly artist and her granddaughter. Somewhat autobiographical, utterly touching, with deceptively simple writing that lingers long.

ITALY

Foucault's Pendulum

His best known novel is perhaps The Name of the Rose, and as 'fun' as that book is, Eco's ability to combine elements of the thriller, the literary novel and historical fiction are never better displayed in this story that's what the Da Vinci code might be if it was (way) smarter and had its tongue in its cheek. The book every tin-foiling, bunker-building, survivalist-loving conspiracy theorist ought to read.

FRANCE

The Outsider - Albert Camus

Sadly, I have only ever managed to read a handful of books in their original language, one being The Summer Book, above, and another being this classic French novel of existential horror, and simmering racism. You'll notice that what links them both is that they are very short. But short novels are often the most powerful - their content is distilled, and hit you harder as a result.

SWITZERLAND

The Vampire of Ropraz - Jacques Chessex

Loosely based on the true story of a serial killer in the Jura Mountains in the early days of the 20th century, this is another short book that punches above its weight, using distancing prose in an almost reportage style that somehow makes the events it describes even more horrific.

POLAND

Who was David Weiser? - Paweł Huelle

So much more than a coming of age story - this mysterious tale is a book about tolerance, friendship and faith. Set in the Poland of the late fifties, a country still very much living with the outcomes of war, it's the story of a strange, charismatic boy with powers no one understands and whose disappearance is never satisfactorily solved.

GERMANY

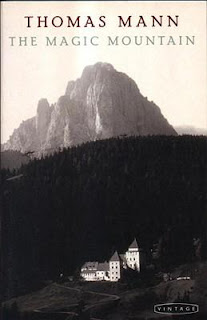

The Magic Mountain - Thomas Mann

In my humble estimation, this is the finest novel ever written and I am going to say nothing about it (or we'll be here all day) apart from the thought that this masterpiece is set in the seven years up to 1914 and therefore the approach of war that will see Europe run with an ocean of blood – to paraphrase Jung's nightmare that was a premonition of European conflict – is never too far away. Look away now if you don't want to read the final line of the book (in the translation by H.T. Lowe-Porter).

"Out of this universal feast of death, out of this extremity of fever, kindling the rain-washed evening sky to a fiery glow, may it be that Love one day shall mount?"

Think it's too much to intimate that we could see war again in Europe? That's what they said after the war Mann was writing about. It's what we said after the second war too. And after that horror, we founded a European community in which conflicts would be settled in debating chambers and courtrooms, as opposed to gas chambers and battlefields. Actual warfare was assumed to be a thing of the past, and then came the genocides of the wars in the former Yugoslavia, and that was only 20 odd years ago.

To end, I've just returned from the American Librarian Association's conference. It was heartening to see how many people were not follwing the EU referendum, but as horrified (and amazed) by the result. They see the obvious implication for their looming presidential election this November, and realise that the same mentality that voted to leave is the same mentality that may elect a ranting racist to the most powerful job in the world. Driven by the same kind of fear-mongering, this is a mindset that refuses to accept that we live in a globally-connected world. We can either enjoy and profit from that cross-culturality, or we can live in fear and conflict.

Had my father lived, (he would have been 100 this year, born during a Zeppelin raid in the first world war), he would be weeping to see the events of the last few weeks. When he died, my mother asked me to sketch a design for a sundial to be set in the grounds of the college he created. The block of slate was duly made in Wales, and dispatched to Kent, inscribed with words she chose; under his name and dates is the following: 'This centre of international friendship is his memorial'. His was work that I find it easy to see as important - not only did his schools teach people English, I saw how they fostered tolerance and understanding.

In my jet-lagged haze, I am trying to tell myself that books are important. That they do have a place in all this; that perhaps, in the long run, they really are the most potent force of all, because they contain ideas, ideas that can change the planet. We know this to be true, or freedom of speech wouldn't be banned in more than half the nations on Earth. As Percy Shelley said, 'poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world'.

So who's right - Mishima or Shelley? Are writers insensitive voyeurs, or honourable philosophers? I guess my view on this can be summed up in this thought about writing by another poet, John Keats, who said a writer spends his or her life trying to work out whether they are the healer or the patient.

The answer, of course, is both.